Making a genetic algorithm to navigate a 2D spacecraft

One of my hobbies is to code algorithms to solve problems on CodinGame and LeetCode. Today, I want to showcase a problem that got my attention here, and my solution using genetic algorithms.

The full project I made is available on my github.

The problem

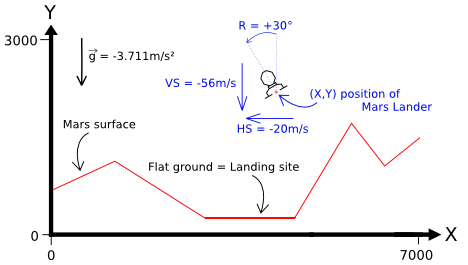

We have a “game” that simulates a free-falling spacecraft. I have to write a program that controls the angle and power of the thrusters. The goal is to navigate it to avoid collision with the land and make it land safely to the target landing zone.

1 game tick = 1 second. Each tick, the game recalculates the position and velocity of the ship, and checks for collision with the land.

At the first tick, the game inputs our program with:

- The vertices that interconnects into segments that shape the land

- The segment with a width of 1000 is the target landing zone

Each tick, the game also inputs to our program:

- The position of the spacecraft

- Its velocity

- The remaining fuel

Each tick, our program must output a pair of value:

- The angle of the thruster (between -90° and 90˚)

- It can change by +/- 15° at most between each tick.

- The power of the thruster (between 0 and 4 m/s²)

- It can change by +/- 1 at most between each tick.

For the rest of this post, let’s refer to a single pair of output as a Ship Control.

In order to “win” at the game, we must:

- Land the spacecraft at the specified landing zone

- Not touch any other surface

- Land with a limited velocity: Less than 20 m/s horizontally speed and 40 m/s vertically

- Land with an angle of 0 (The spacecraft must be upright)

Why genetic algorithm?

The reason this problem had my attention is how it differentiates itself from some easier methods, as it involves trial and error, rather than directly computing an unique satisfying solution.

The first and obvious method I would think of to solve this is to use several conditions, whose parameters are adjusted manually by trial and error. For example, we could think of setting the angle to 0 and the power to 4 when close to the ground by a certain distance, or setting the angle to 45° when the target is towards the left.

But I would end up defining a lot of conditions with several parameters, and that would at best only work for the cases I tried on.

What to do then? How about mathematical optimization? I know that I can put everything under an equation and establish a cost function to minimize? But that wouldn’t work either since the unknown is a vector of hundreds of Ship Controls, spanning throughout all the ticks of the simulation.

Looking at the main page of the problem website, there is a method that is suggested: genetic algorithm. That is a metaheuristic technique, which is a degree higher than mathematical optimization.

From the Essentials of Metaheuristics introduction:

Metaheuristics are applied to I know it when I see it problems. They’re algorithms used to find answers to problems when you have very little to help you: you don’t know beforehand what the optimal solution looks like, you don’t know how to go about finding it in a principled way, you have very little heuristic information to go on, and brute-force search is out of the question because the space is too large. But if you’re given a candidate solution to your problem, you can test it and assess how good it is.

Due to the complexity of the problem, it’s safe to say that metaheuristics would be made good use here. I don’t know which technique would be better (Tabu search? Ant colony optimization?), but GA seems good here.

Encoding the chromosome

Each generation contain a set of solution (Chromosome). Each chromosome is evaluated and is affected a score that depends on how close they are to the winning conditions. The next generation is created depending on who has the highest score with the process of crossover and mutations. We repeat until we get a chromosome that meets the “win” conditions.

In order to evaluate the chromosomes, we need to predict their trajectory. To do that, I had to rewrite the simulation used by game, as it is not provided. This was done easily by comparing the execution of a set of Ship Controls to my simulation and the game’s simulation.

A chromosome is basically a sequence of Ship Controls.

How long is that sequence?

We don’t know. The simulation can last from few seconds to several minutes depending on the chromosome and the initial situation.

I decided to make all the chromosomes the same arbitrary size. If we run out of Ship Controls before the simulation ends, then we assume that the rest of the Ship Controls have the same value (e.g. angle = 0 and power = 4).

So the plan is for each chromosome to represent a sequence of Ship Controls, right? The the most obvious way to represent it would be:

struct Allele_V1{

int angle; // Between -90 and 90

int power; // Between 0 and 4

}

using Chromosome = std::vector<Allele_V1>;

However, between two ticks, the angle can only vary by 15° at most, and the power by 1. This would mean that our alleles have a range of value that would give the same outcome.

chromosome0[0] = {15, 2}; // Ship's state is {15, 2}

chromosome0[1] = {60, 4}; // Ship's state is {30, 3}

chromosome1[0] = {15, 2}; // Ship's state is {15, 2}

chromosome1[1] = {30, 3}; // Ship's state is {30, 3}

// chromosome0 and chromosome1 would result in

// the same simulation despite having different values

So instead of making our chromosomes represents the Ship Controls in absolute value, let’s make them represent their variations.

struct Allele_V2 {

int d_angle; // between -15 and 15

int d_power; // between -1 and 1

}

Much better.

There is a different approach that I tried in order to compress more data into a single chromosome. Basically, each allele defines a duration d_t during the simulation that outputs the same Ship Control.

struct Allele_V3 {

int d_t;

int d_angle;

int d_power;

};

This encoding didn’t work very well. Is it because it makes the crossover made too much of a mess? Or did it make the space of solutions too large? I’m not sure, but I eventually reverted to Allele_V2.

Allele_V2 really is the most logical way to encode the chromosomes, but as I had trouble to make the crossover and mutation operations that use it, I decided to explore more.

I decided to make the solution space as small as possible. So I settled on a minimal binary representation.

struct Allele_V4 {

bool eAng;

bool dAng;

bool dPow;

};

With the interpretation being:

| Angle change | eAng | dAng |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | X |

| +15 | 1 | 1 |

| -15 | 1 | 0 |

| Power change | dPow |

|---|---|

| +1 | 1 |

| -1 | 0 |

This representation compresses the data as much as possible, with the downside being that not all possible solutions will be explored. (For example, retaining an angle of 5 and a power of 3 through several ticks is not possible).

At first, I omitted eAng, meaning that the angle would always vary left or right depending on dAng. However, I found out that to beat gravity, the ship must have a non varying angle so that it could throttle upwards properly instead of wobbling.

Another advantage of this representation and the main reason I didn’t settle with Allele_V2 is the easy choice and implementation of genetic operators for crossover and mutation.

Bitwise genetic operators

Instead of making the Chromosome use an Array of Structure (vector<Allele_V4>), let’s make it use a Structure of Array:

static constexpr size_t NUM_ALLELE{ 128 };

using BitSet = std::bitset<NUM_ALLELE>;

class Chromosome {

BitSet eAng_;

BitSet dAng_;

BitSet dPow_;

// ...

};

The good thing with this binary representation of chromosome is that we can easily use bitwise operators to implement most genetic operators.

Chromosome::crossover(Random& rand,

const Chromosome& p1,

const Chromosome& p2,

Chromosome& c1,

Chromosome& c2)

{

static std::uniform_int_distribution<size_t> pt0{ 1, NUM_ALLELE - 2 };

size_t pt{ pt0(rand.get()) }; // Crossover point between 1 and NUM_ALLELE-2

BitSet fil{ BitSet{ 0 }.flip() << pt }; // 0b111..1100..0000

c1.eAng_ = p1.eAng_ & fil | p2.eAng_ & ~fil;

c2.eAng_ = p2.eAng_ & fil | p1.eAng_ & ~fil;

c1.dAng_ = p1.dAng_ & fil | p2.dAng_ & ~fil;

c2.dAng_ = p2.dAng_ & fil | p1.dAng_ & ~fil;

c1.dPow_ = p1.dPow_ & fil | p2.dPow_ & ~fil;

c2.dPow_ = p2.dPow_ & fil | p1.dPow_ & ~fil;

}

We can also generate the initial random population by generating random integers:

BitSet Chromosome::randombs(Random& rand) {

using Assigner = uint64_t;

static constexpr auto SZBS{ NUM_ALLELE }; // Number of bits in a Chromosome (128)

static constexpr auto SZAS{ sizeof(Assigner) * 8 }; // Number of bits for the generated integer (64)

static constexpr auto NUMIT{ SZBS / SZAS }; // Number of iterations (2)

static constexpr auto MXAS{ std::numeric_limits<Assigner>::max() };

static std::uniform_int_distribution<Assigner> rand0{ Assigner{ 0 }, MXAS };

BitSet ret{ rand0(rand.get()) };

for(auto i{ NUMIT }; i != 0; i--) {

ret <<= SZAS;

ret |= rand0(rand.get());

}

return ret;

}

Fitness evaluation

Evaluating the chromosome was done by comparing the chromosome’s of the landing conditions (position, speed, angle) and the expected landing.

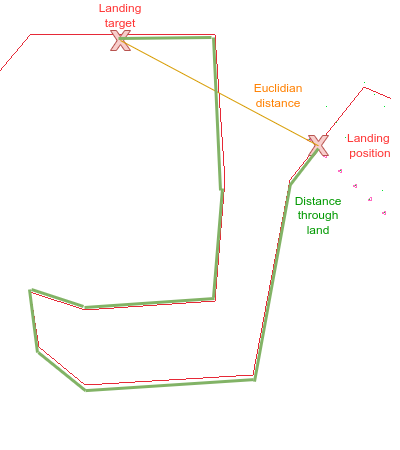

In order to take into account obstacles, and avoid the distance calculation to fall into a local minima, we calculate instead the distance of all the land segments between the landing position and the landing target:

The score is cacluated with a code that looks like this:

float evaluate(Chromosome const& chr) {

Simulation simu(chr);

auto state = simu.getFinalState();

float score = 0;

// More penalizing if the ship didn't touch the target.

if(state.distanceThroughLand < 500)

score -= state.distanceThroughLand /100;

else

score -= state.distanceThroughLand;

// Change in velocity will not give a better score if already below a certain value

score -= max( abs(state.velocity.x), 15 );

score -= max( abs(state.velocity.y), 35 );

score -= abs(state.angle)/90;

if(state.succesfulLanding())

score += 10000;

return score;

}

Double buffered population

We don’t need to store every single generation in the memory. In fact, all we need is the current generation, and the previous one that will be generated from.

I implemented a template class in order to easily switch between the current and previous population, without additionnal copies in memory. This prevents reallocation, by reusing already constructed objects.

template<class T>

class DoubleBuffer {

bool idx_;

T buff_[2];

public:

DoubleBuffer() : idx_{ false } {}

auto&

curr() { return buff_[!idx_]; }

auto&

prev() { return buff_[idx_]; }

void

flip() { idx_ = !idx_; }

};

Which can be used for example like this:

DoubleBuffer<Population> population_;

void processNextGeneration() {

population_.flip();

population_.curr().copyElites( population_.prev() );

// etc...

}

Time shifting the simulation

There is an important rule mentioned within the problem

Response time per turn ≤ 100ms

This means that every tick, my program has 100ms to respond with an output of a Ship Control. I’ll be the first to admit, my program is not nearly close to fast, and can’t find a solution in this short amount of time.

However, by adapting the algorithm, we can go around that constraint, and even use it to our advantage.

The idea is for each tick, we run the algorithm for a few generations, output the first Ship Control of the best chromosome we currently have, and then commit to it in our simulation:

- Change the initial simulation state to the chosen Ship Control

- Shift all bits in the chromosomes

So our main loop will look like something like this:

GeneticAlgorithm ga;

ga.setInitialState(position, velocity, ...);

int generationsPerIteration = 10;

while(!ga.done()) {

ga.execute(generationsPerIteration);

auto shipControl = ga.getShipControl();

cout << shipControl << endl; // Output the ship control to the game

ga.changeInitialStateFromSC(shipControl);

}

void Chromosome::timeShift(size_t t, Random& rand)

{

static std::bernoulli_distribution b{ 0.5 };

eAng_ >>= t;

dAng_ >>= t;

dPow_ >>= t;

// Generate random bits for the last ticks

for(size_t i{ NUM_ALLELE - t }; i < NUM_ALLELE; i++) {

eAng_[i] = b(rand.get());

dAng_[i] = b(rand.get());

dPow_[i] = b(rand.get());

}

// [...]

}

The trick here is to set the value of generations per iteration low enough to avoid making the program timeout.

We now have an algorithm capable of running step by step, that gradually commits to a trajectory. This also conveniently solves the problem I mentioned earlier about Chromosomes having a sequence of Ship Controls that is too small.

Results

Timing the execution of my code running locally, we get the following results:

| Input | Execution time (seconds) | Maximum generation |

|---|---|---|

| input1.txt | 0.36 | 88 |

| input2.txt | 0.52 | 126 |

| input3.txt | 0.85 | 237 |

| input4.txt | 0.46 | 96 |

| input5.txt | 0.44 | 82 |

| input6.txt | 0.26 | 47 |

| input7.txt | 2.39 | 558 |

An algorithm that lasts for several seconds is not very convenient, and I’m sure I could easily optimize it. But that’s not my goal, what matters is that it finally works.

Let’s see how it runs input7:

References

- Di_Masta - A Dedicated Landing with a Genetic Algorithm - A post that inspired this project.

- Sean Luke - Essentials of Metaheuristics